The Slow Death of the Contemporary Art Gallery

A hunger for new voices and unconventional methods is reshaping the market.

The contemporary art gallery as we know it is dying. In cities like New York and Los Angeles, dedicated spaces that once buzzed with foot traffic and formal openings are now struggling with rising rents and changing expectations. The old model, where a gallery does everything for its artists, feels like it’s falling apart.

Big gallery chains, the ones built on endless art fairs, multiple cities and huge rosters of artists, are losing their grip. Last month, Tim Blum announced he would close his Blum & Poe galleries in L.A. and Tokyo and even stop plans for a new one in Tribeca. He was blunt about the reason: “This is not about the market. This is about the system,” he told ARTnews, pointing out that collectors have more power than ever to negotiate. His decision echoes a wider feeling across the industry with many giving up on the idea of building giant gallery empires.

You can see this shift happening at major events. The latest Art Basel confirmed that galleries are showing more mid-priced work, not just the massive, ultra-expensive pieces they once counted on. A recent report from Art Basel and UBS showed that while the overall art market shrank last year, the number of actual sales went up. It’s a clear signal that the business is no longer just about a small group of big spenders, it’s now about reaching a wider audience at lower price points.

“The old model was built on scarcity and prestige. The new one runs on access and attention.”

A significant force behind this change is the shifting demand for different types of art. The once-dominant “blue-chip” artists, masters whose work commanded staggering prices, are no longer the only game in town. Collectors are increasingly turning their attention to “red-chip” artists, a new class of talents whose value is built on viral hype and cultural relevance rather than institutional endorsement. These artists are attractive for two main reasons: their work is often more accessible and affordable, and it brings fresh, diverse cultural perspectives that feel relevant and exciting to a global audience.

This hunger for new voices and unconventional methods is reshaping the market. A key example is Olaolu Slawn, a London-based artist who sold out his solo show, I present to you, Slawn, at the Saatchi Yates gallery in 2024 by creating and selling 1,000 individual, more accessible pieces, an approach that challenges the fine art world’s focus on scarcity and prestige.

A separate but related trend sees celebrities entering the art market with their own work, often commanding high prices based on their fame. Actor Adrien Brody is a notable example. His art, which he described is about celebrating the little nuances in life has sold for significant amounts, as per a convo with Interview Magazine. For instance, a painting he created of Marilyn Monroe was sold at a Cannes gala auction for $425,000 USD, illustrating how star power can directly translate into commercial value. However, his work has drawn sharp criticism from the industry, with critics often labeling it as kitschy and derivative. One critic writing for ARTnews described his work as having a “faux naïve aesthetic” and “mediocre production value,” while others have accused him of cheaply appropriating the styles of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol.

As the old guard shrinks, smaller galleries are finding new ways to thrive. In New York, Tiwa Gallery shows self-taught artists in a relaxed space, rejecting flashy marketing. Portland’s Landdd combines Latin American crafts with immersive events. In L.A., Marta gallery blends art and design right into everyday life. These new spaces care more about quiet, genuine connection than putting on a spectacle.

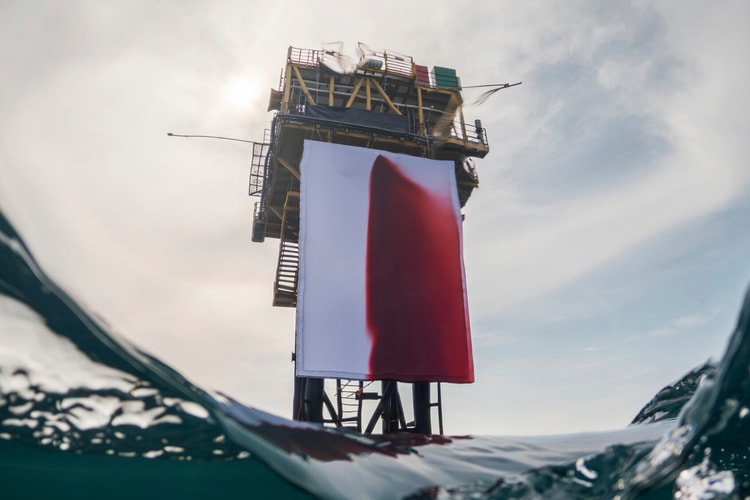

Retail is also becoming a new kind of gallery. Stores like South Korea’s Gentle Monster and London’s Dover Street Market are blurring the lines between art and commerce, transforming shopping into an immersive cultural experience. Gentle Monster’s stores are famous for their fantastical, ever-changing installations, from surreal kinetic sculptures to robotic figures that draw in visitors who are just as interested in the art as they are in the eyewear. Dover Street Market, founded by Comme des Garçons’s Rei Kawakubo, is a “beautiful chaos” where each brand and artist is given a dedicated space to create a unique installation, turning the store into a constantly evolving exhibition. By blending high-end retail with cutting-edge art and design these spaces offer a new kind of public access to creativity, making the gallery experience a part of a commercial transaction rather than a separate cultural outing.

“If your space is fueled by DJs and cocktails, maybe it isn’t really a gallery anymore.”

It’s clear that going to a gallery is no longer the only way to see or buy art. Today, buyers can just scroll on their phones and purchase work directly from studios or social media. This instant access has replaced the slow dance of white-cube shows and champagne previews. Some galleries are trying to keep up, creating online art drops and hosting pop-ups in different retail spaces. But others are pushing back, as one veteran gallerist puts it: if your space is fueled by DJs and cocktails, maybe it isn’t really a gallery anymore.

Art isn’t disappearing. It’s just moving, becoming more accessible and less tied to one physical location. The old model was built on scarcity and prestige. The new one runs on access and attention. The question isn’t whether galleries will survive, but which ones can change fast enough to matter.