For Kennedy Yanko, gravity is more of a suggestion than a rule. The St. Louis-born artist has mastered the art of sculptural alchemy, building a name for herself through her signature paint skin works – sheets of dried paint take on a leathery alterlife, later draped atop metal salvage – which earned their own double showcase in New York earlier this year. While garnering a reputation as a vital voice in the medium, Yanko insists, “I’m a painter that makes sculpture.”

Now, she’s bringing that claim full circle with her latest exhibition at Pace Prints. On view through October 4, Without Gravity marks a sort of 2D homecoming for the now Miami-based artist, as she brings forth a family of multilayered compositions, echoing the gestural drama and perceptual essence of her three-dimensional paintings while landing in a previously unexplored terrain.

Catalyzed by her Rubell Museum residency showcase during Art Basel 2021, Yanko’s ascent into art stardom is one defined by “movement and momentum,” both in the journey itself and the works that carried it. Pouring, staining, sculpting pulp into the shape of possibility, her first body of paper works evoke a sculptural physicality, yet exist on their own terms. Tracing arcs of energy, immediacy, and touch, Without Gravity is less about what paper can hold than what it can release.

For the latest edition of Hypeart Visits, we caught up with Yanko to discuss the makings behind her Pace Prints show, making her mark as a living artist and the performance background that drives it all.

“There’s an immediacy that paper satisfies and figuring that out was a really delicious process.”

For Without Gravity, you opted to return to 2D works, after numerous paint skin sculpture showcases. Can you walk us through that decision, and, to put it broadly, what was that return like?

I hadn’t worked with paper pulp before, and I was very intrigued. I was nervous to work in a new medium, but walking into the unknown is when I thrive the most. When my eyes are closed, and I’m touching, feeling and trying to figure my way around — it’s one of my favorite things. In this particular capacity, though, I was held by the brilliant printmakers at Pace Prints who were really able to help me translate my vision. They knew the material like the back of their hands.

It’s funny because my niece came in and saw the resemblance between these works and my paintings from a decade ago. They share the same color and sensation. Working in sculpture can be an excruciatingly tedious and logistical process. Being a painter with a background in momentum and movement, it felt great to get back to working like this. In a way, I kind of longed for that. There’s an immediacy that paper satisfies and figuring that out was a really delicious process.

Viscerality, choreography and sensation all play pivotal roles in your practice. How would you describe feeling or sensation when you know a work is complete?

A lot of that language comes from my time at The Living Theater, a famous anarchist pacifist experimental theater company. The choreography in the work came from the methods that I learned in performance and political theater with Judith Malina. That’s where I learned how to pull something from inside of myself out.

For me, that feeling is really strange and hard to describe. The word that comes to mind is “fullness” — the visual feeling of sitting around a table with your favorite people. Everything is complete. Everything is whole. Everything is right. It’s about being able to look at something until it feels that way.

“I really thrive off of obstacles and often see them as a director, so whenever I’m challenged by something, it’s just an opportunity for me to sit still, look and wait for the answer.”

Did you have any performance background prior to Living Theater?

Not at all. I ended up there after I dropped out of the San Francisco Art Institute. Poets, writers, musicians, actors — all different kinds of people were at the Living Theater. It was really an incubator for thought.

Part of learning and being there was working toward developing an intuitive muscle and becoming attuned to signals inside myself. A lot of those techniques were practiced in performance, in response to an audience member or just fully engaging with being human. It’s where I understood what it meant to be a living and working artist.

Seeing how your experience at Living Theater carries into your work today, were there any newly developed techniques from this show that you want to explore further in the future?

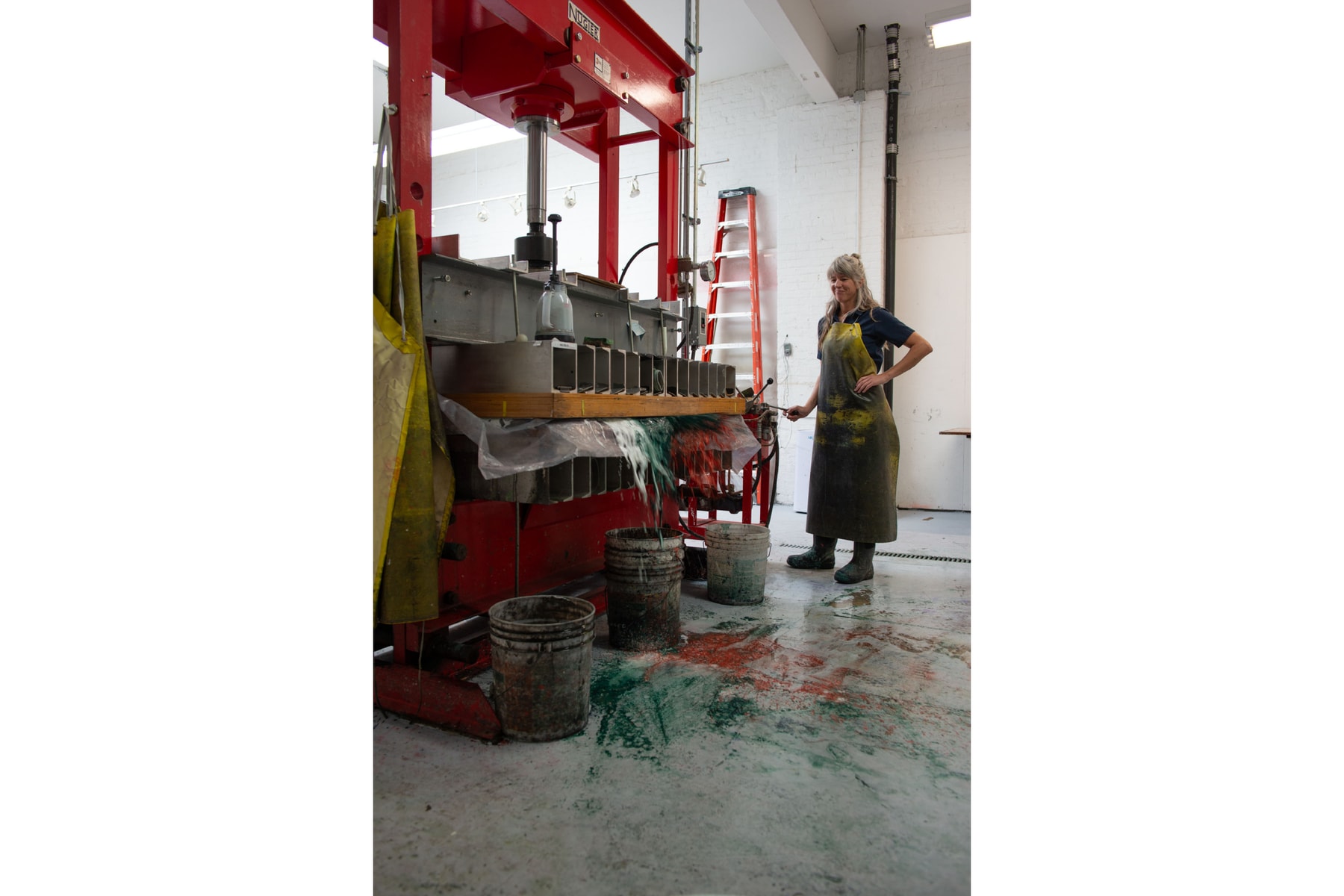

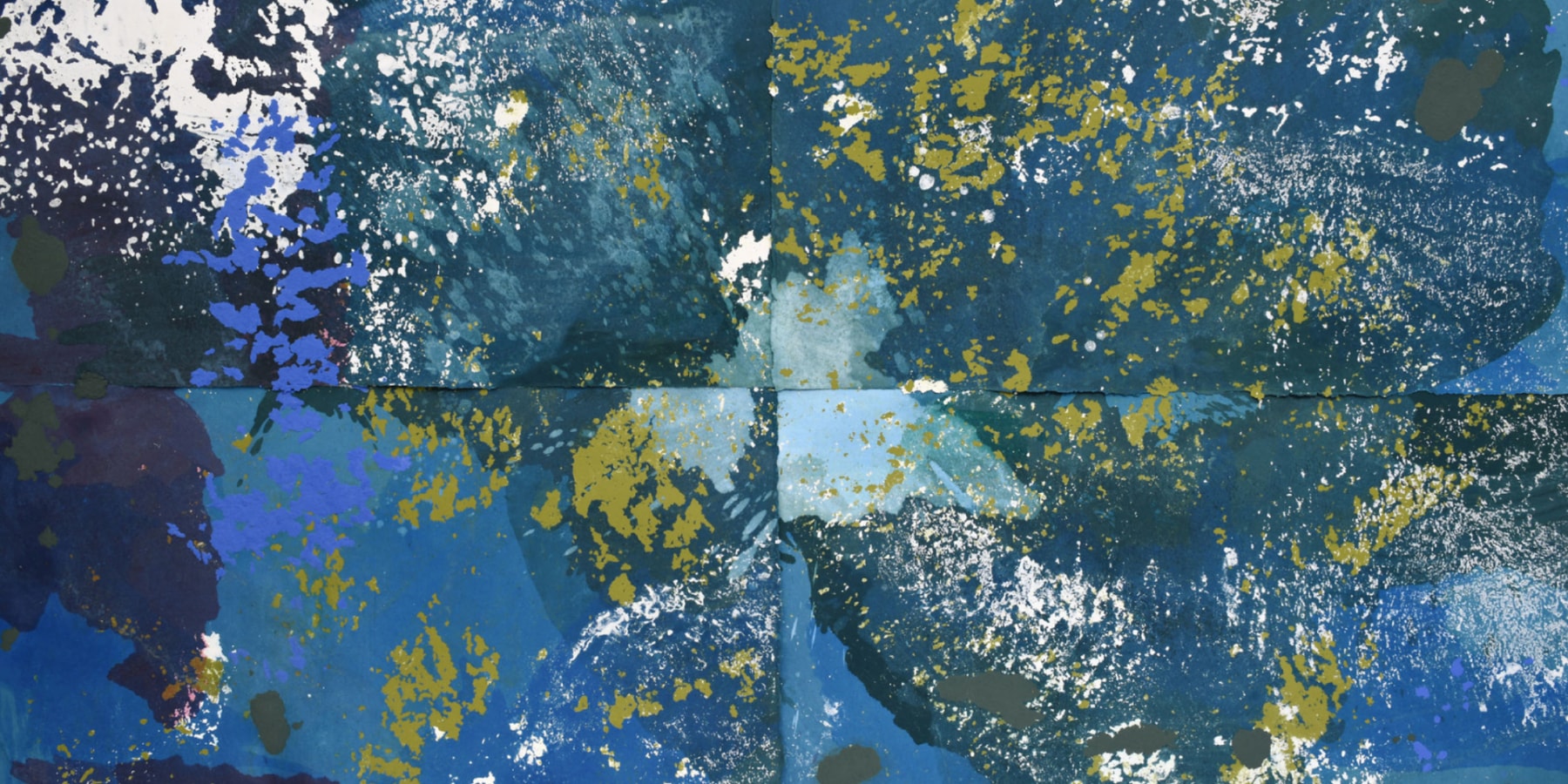

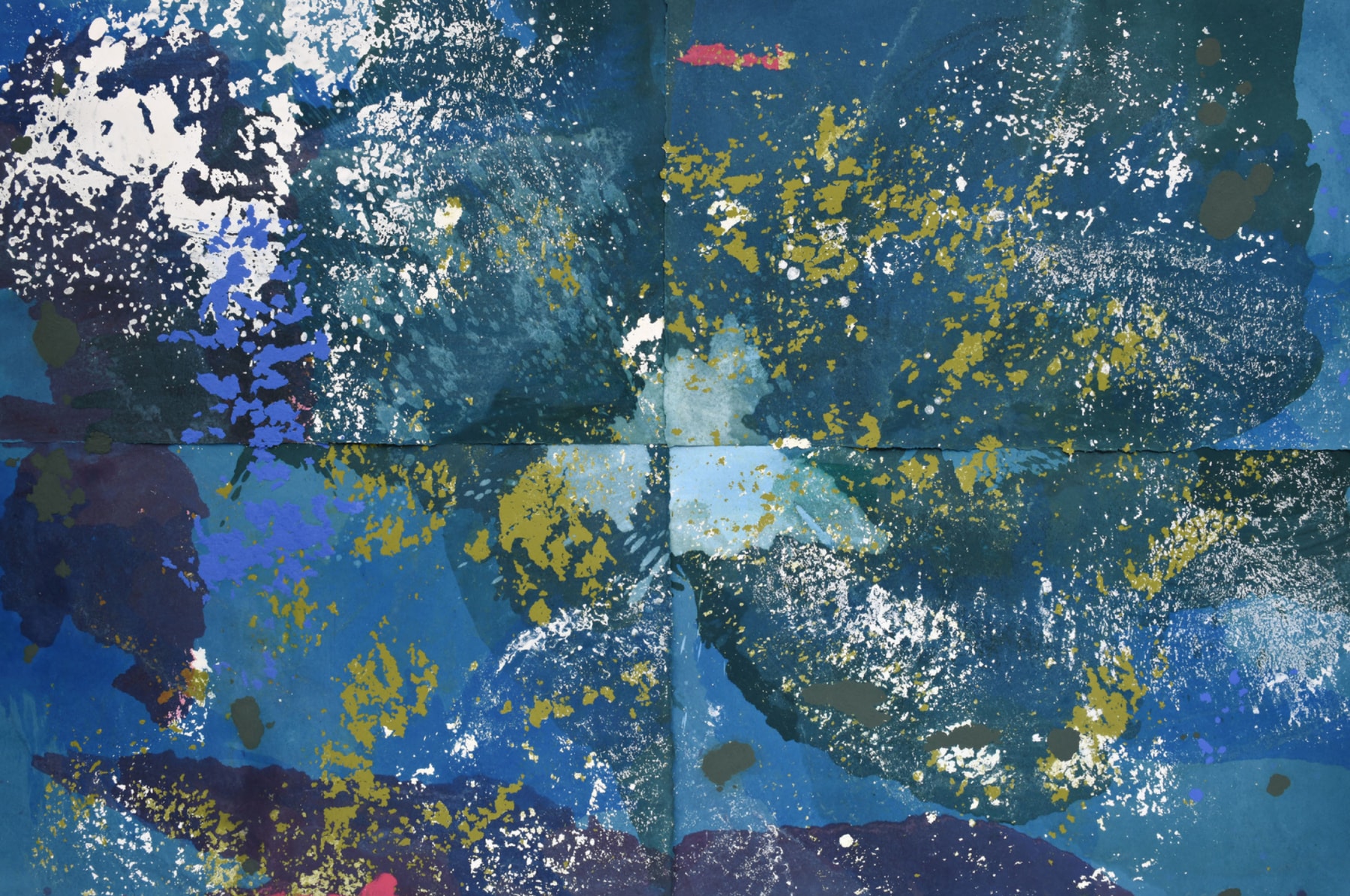

First we did explosions. I poured pulp and took it under the eight ton press, pressing down really fast until it exploded. This was the first time they’d ever done that in the studio. It created these really beautiful, almost impressionistic points that we used as a transfer onto the paper.

Then I started using my arm to draw directly through the pulp. This made a pattern that, on the surface, almost looked like tire marks. It’s a signature technique that I’m going to keep exploring — different ways my hands can separate and interact with the pulp to create these unique “constellations.”

The technique that really got me where I wanted to go didn’t come until the end of my time there. I was having trouble getting the right hues and saturation, so as soon as I did my first press, I’d pour pigment directly onto the papers. Throughout my career, pouring has been such a big part of my discovery process. A lot of that was from my own painting practice, but I was also thinking about Helen Frankenthaler and her pours – how revolutionary they were to abstract painting, their simplicity and power. They became a really nice compositional grounding for how I approached the transfers.

You’re also playing with time and permanence in maybe a different or new way.

That’s exactly how the title of the show and the sensation of the work happened. It really created this moment, this sensation of something being still in time and floating without gravity.

Were there any moments in experimenting that were particularly unexpected or challenging? Or was it more about leaning into an element of chance?

The process is what makes it fun. I really thrive off of obstacles and often see them as a director, so whenever I’m challenged by something, it’s just an opportunity for me to sit still, look and wait for the answer.

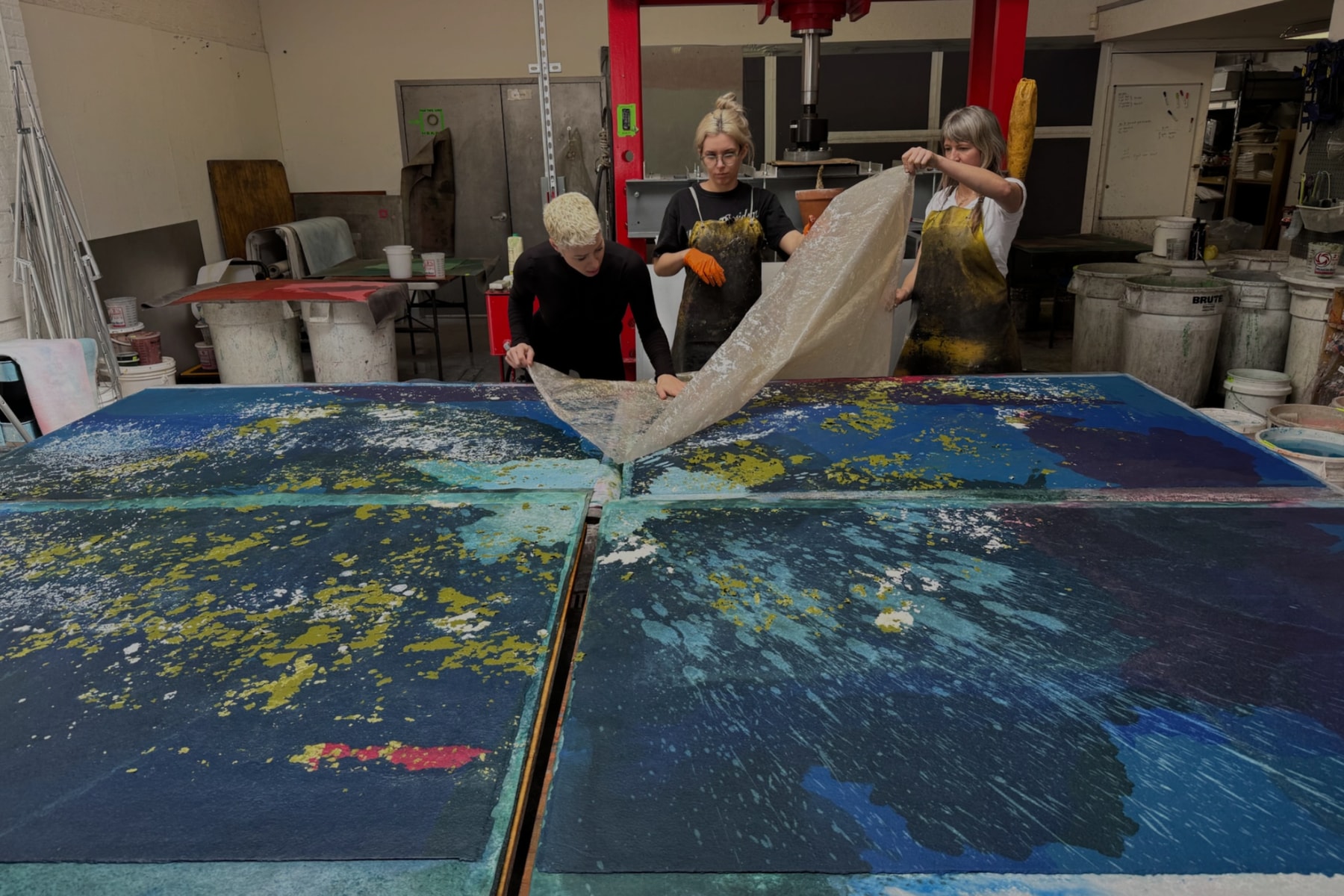

What was it like working in Pace’s wet paper studio with a new team?

Being with the women at the studio was like being at summer camp. We had the best time. There was a kind of connectivity and fluidness to how we were all working together. We have to transfer things at the same time and just be super in tune with each other to make sure things happen the right way. It was a dream. I’ve never had so many people working with me before and to have support like that.

Without Gravity was developed in four weeks over the course of a year. Could you walk us through what all of those stages looked like?

They were all about like three months apart, which I liked because it gave me a moment to step back and think about it. The first week was really about understanding the material – how it works, how it moves, what it does. Maybe a couple of those pieces made it to the finish line, but it was more about experimentation.

The second time, we were able to really find a nicer rhythm. We had the explosions down and I started developing the arm drawing, envisioning how I wanted to layer things.

The third time, we finally figured out the colors. I wanted the hues to be deeper and more saturated, which is when I started doing my pouring. It created these really incredible shadows of light and dark that added a lot more density to the work, and using black introduced a much-needed grittiness.

The last time we came in, we just kind of really fleshed out that process and made the best work that really solidified the direction the work would go in.

“As a living artist, it’s important that my story is told in my own voice – to make what I want to say clear in my work, not just what others want to understand it as. As a young, ambitious woman, that’s something I’ve been fighting for.”

In addition to exhibiting your works, you’ve gotten to flex your curatorial muscles more, first with your double showcase earlier this year, and now the Pace show.

I love art because it brings so many different kinds of people together. It’s really beautiful to be able to weave a narrative between masters and younger artists and contextualize work in a way that maybe a curator or journalist wouldn’t otherwise see.

As a living artist, it’s important that my story is told in my own voice – to make what I want to say clear in my work, not just what others want to understand it as. As a young, ambitious woman, that’s something I’ve been fighting for.

In doing these shows, I get to hold space for the people who have worked hard to create this language and have made this space for me, and showcase the work of my peers and the people coming up around me as well.

Do you have a favorite living artist that you look up to?

That question is hard. It’s like asking, ‘Who’s your favorite parent?’ My references are kind of crazy. They go from the Light and Space artists to Dutch Reformation painters, to abstract expressionists, to the surrealists. There’s a lot of artists that have different places in my work, but here are some big ones that I reference a lot: Leonardo Drew for his explosions. Torkwase Dyson for her development of “Black Compositional Thought.” Ann Hamilton, the way she approaches environment, and Olafur Eliasson, who uses science and conversations of consciousness to expand that dialogue of abstraction.

“There is so much power in exploration – for fun, for healing, for expansion. It’s in following those desires that I find my best and most transformative breakthroughs.”

You’ve had a lot of big projects unfold in the last year. From creating and exhibiting your works, to curating others’, what has it been like to work in all registers of your practice at once?

I wear 30 different hats everyday, so it’s always something new. I started the Without Gravity before I started Retro Future and Epithets, so a lot of those transfers and painterly gestures started coming out in my paint skins. I did a show booth with James Cohan at Frieze London – my first presentation of painted paint skins, since 2012 – and it gave me the confidence to bring my painterly qualities to my sculptural practice again.

When I’m moving and activated, that’s the only way I can think. I always have a ton of tabs open in my head, but it’s nice to go back and forth, and take a break for a second to let things resonate and breathe. I really enjoy working like that and that’s how I’ve always done it. Whether it’s working on a performance or film or painting, there’s always a lot of different things going on. Having space from different mediums is what keeps me really invigorated with them.

Has building out this show brought up any reflective insights about your career or path as an artist?

For me, and for artists more generally, it’s really a privilege to get to experiment across mediums. When I first started working in metal, I never planned on bringing it into my practice. I was depressed and bored and just needed something else to do – I wasn’t intentionally trying to figure something out. There is so much power in exploration – for fun, for healing, for expansion. It’s in following those desires that I find my best and most transformative breakthroughs.

All images courtesy of Pace Prints