Written by Charlie Kane for Hypeart

The early internet is back—or at least, how it looks. Pixelated fonts, chaotic cursors and glitchy graphics have become popular once again amid a wave of Y2K nostalgia. The lo-fi charm of late-’90s and early-2000s digital culture has become a visual language of its own: clunky on purpose, retro without the dial-up. But much of the revival stops at the surface. The nostalgia is easy. The critique is missing.

Yehwan Song’s work doesn’t stop there.

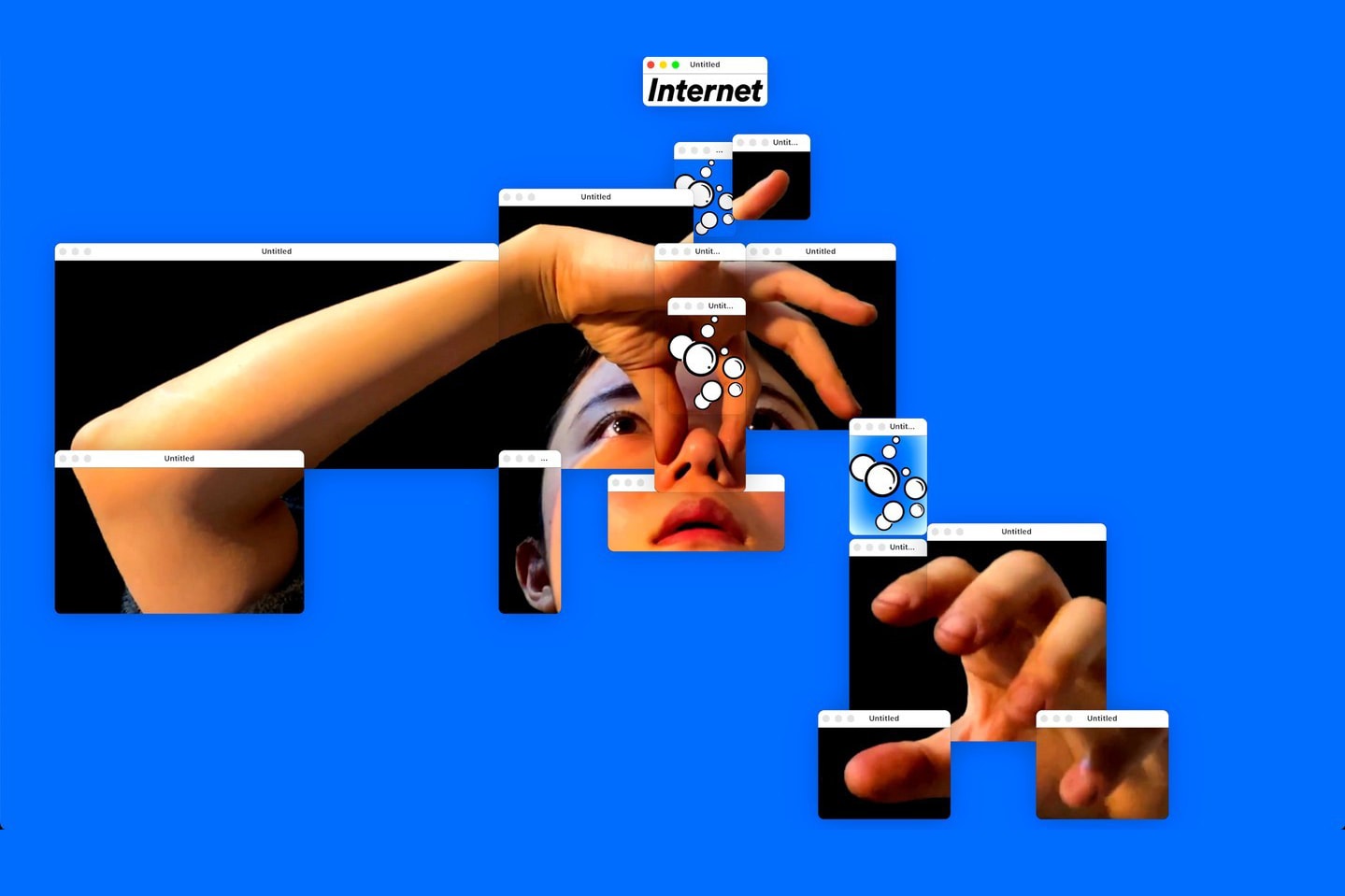

While others borrow the web’s early graphic language, Song returns to the instability of that era, when the internet felt messier, more personal and less predictable. A Korean designer, artist, and developer, she’s spent the past several years building experimental websites and installations that resist the polish of the modern-day algorithmic web. Her projects disrupt the viewing experience, reject smooth navigation and fracture expected UI behavior. They ask what we lose when digital spaces are flattened into seamless feeds that demand passive scrolling.

For Song, the internet didn’t always feel this way. “The internet used to feel freer,” she said. “You could explore, get lost and stumble into something unexpected. I think it’s important to bring that up and ask—where are we now and is this the environment we wanted?”

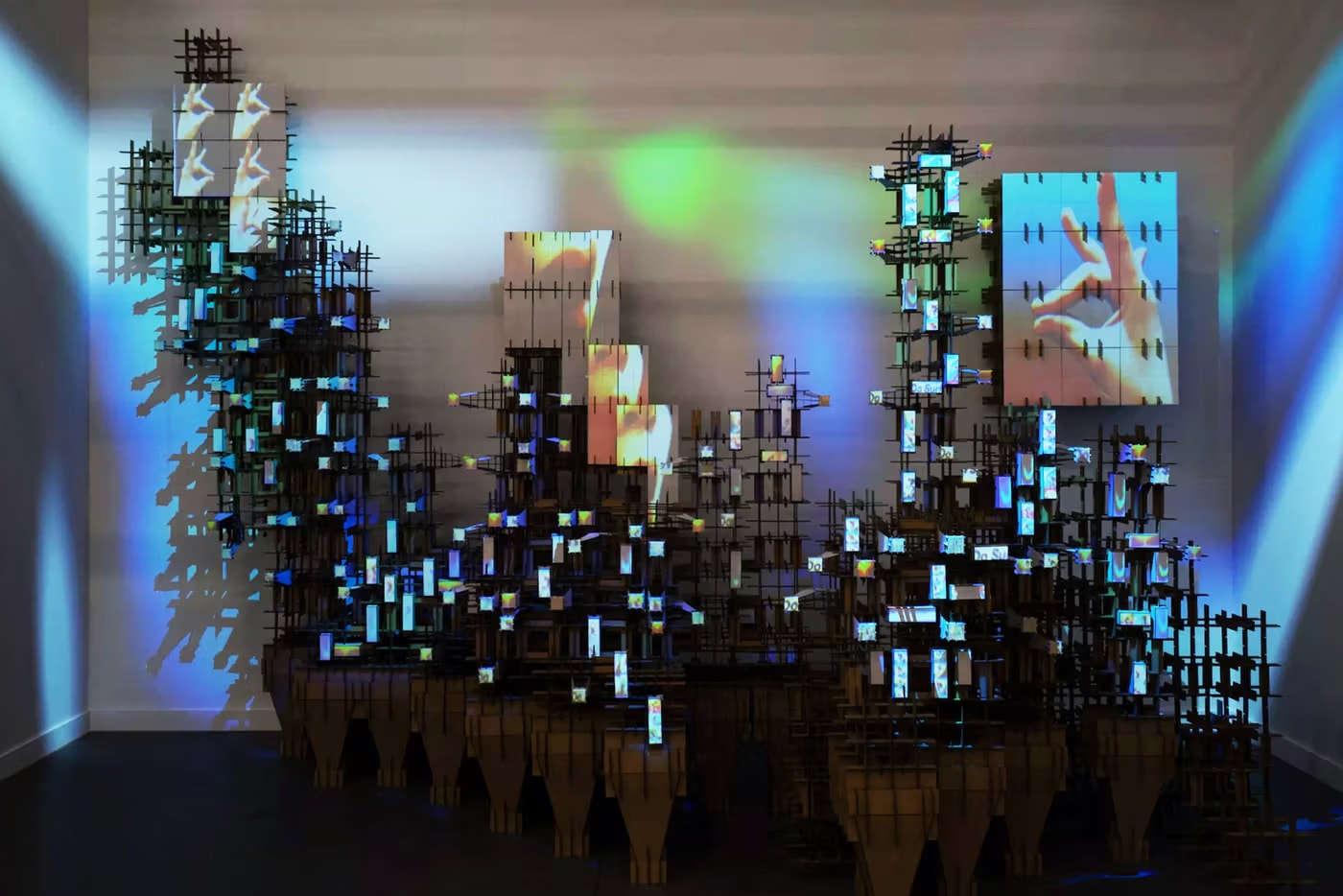

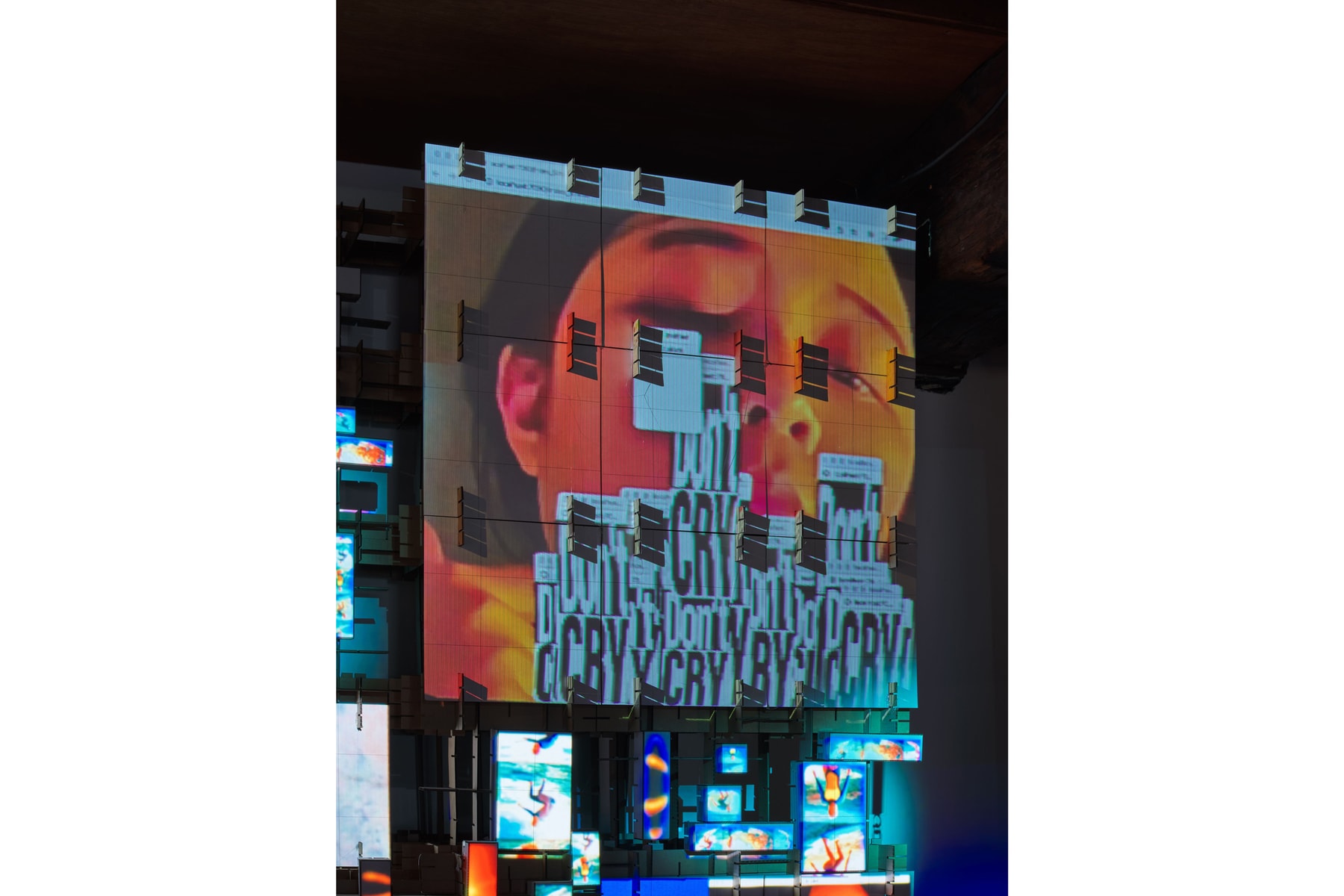

At this year’s Frieze New York, which ran from May 7 to 11, Song brought that interrogation into a physical space. Her installation, “The Barnacles 따개비들,” continues a body of work she calls The Internet Barnacles 인터넷 따개비들—sculpture and video installations that explore how we cling to digital systems and how those shifting systems quietly steer us. The series began with an earlier version in January, shown at G Gallery in Korea, where barnacle-like structures were attached to an abstract, rock-like form. In this new iteration, the imagery shifts as the barnacles now cling to the hulls of ships. Like drifting larvae that eventually anchor, Song comments on how these digital systems subtly reshape users as they become increasingly entangled in algorithms, surveillance and data extraction.

“The Barnacles”—an evolution of Song’s latest exhibition, Are We Still (Surfing)? at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn—shifts from browser-based experiments to immersive kinetic installations. There, projections rippled across modular cardboard forms, transforming the interface into something spatial and unstable. It looks like a glitch made solid. Or a screen you didn’t mean to fall into.

“The Barnacles” deepens that exploration. You don’t scroll past it—you circle, pause and shift your body to catch the images as they scatter. “The internet started as a place to connect people and share many different opinions,” Song said. “But now, with all this optimizing, we ignore that. Everything starts to look the same—icons, formats and users.”

In the weeks leading up to Frieze, Song juggled two projects, finalizing her installation in Korea while preparing to fly to New York. During our late-night video call, the hum of machines filled her studio.

“Is it too loud?” she asked, eyes tired but focused, speaking through the last-minute rush. Even through the screen, her themes—disruption, friction, disorientation—cut through. The call glitched once, dropping her audio. Her backdrop was blurred, while the background hum was silenced by noise cancellation. No smooth interface. No polished ease. Just the real mess of building something that refuses to be easy.

“The internet starts speaking with one voice, giving us answers that seem universal, but it erases the fact that so many people built this space together.”

Song didn’t begin her practice with installations. She trained as a graphic designer, working on visual layouts and digital surfaces. But as she spent more time online, she wanted to understand what lay beneath the clean interfaces she helped shape. She taught herself to code before enrolling in the School for Poetic Computation, where she studied the structure, history, and power embedded in digital systems.

“The internet in Korea is so English-dominant. Even the coding languages are based on English,” she explained. “So I started to think: who is this really for? There are huge differences between users, but we weren’t considering that as designers. We were building for one kind of user—the one who already fits the system.”

That realization continues to shape her work. “What scares me most is how quickly we forget there are diverse users,” she added. “The internet starts speaking with one voice, giving us answers that seem universal, but it erases the fact that so many people built this space together.”

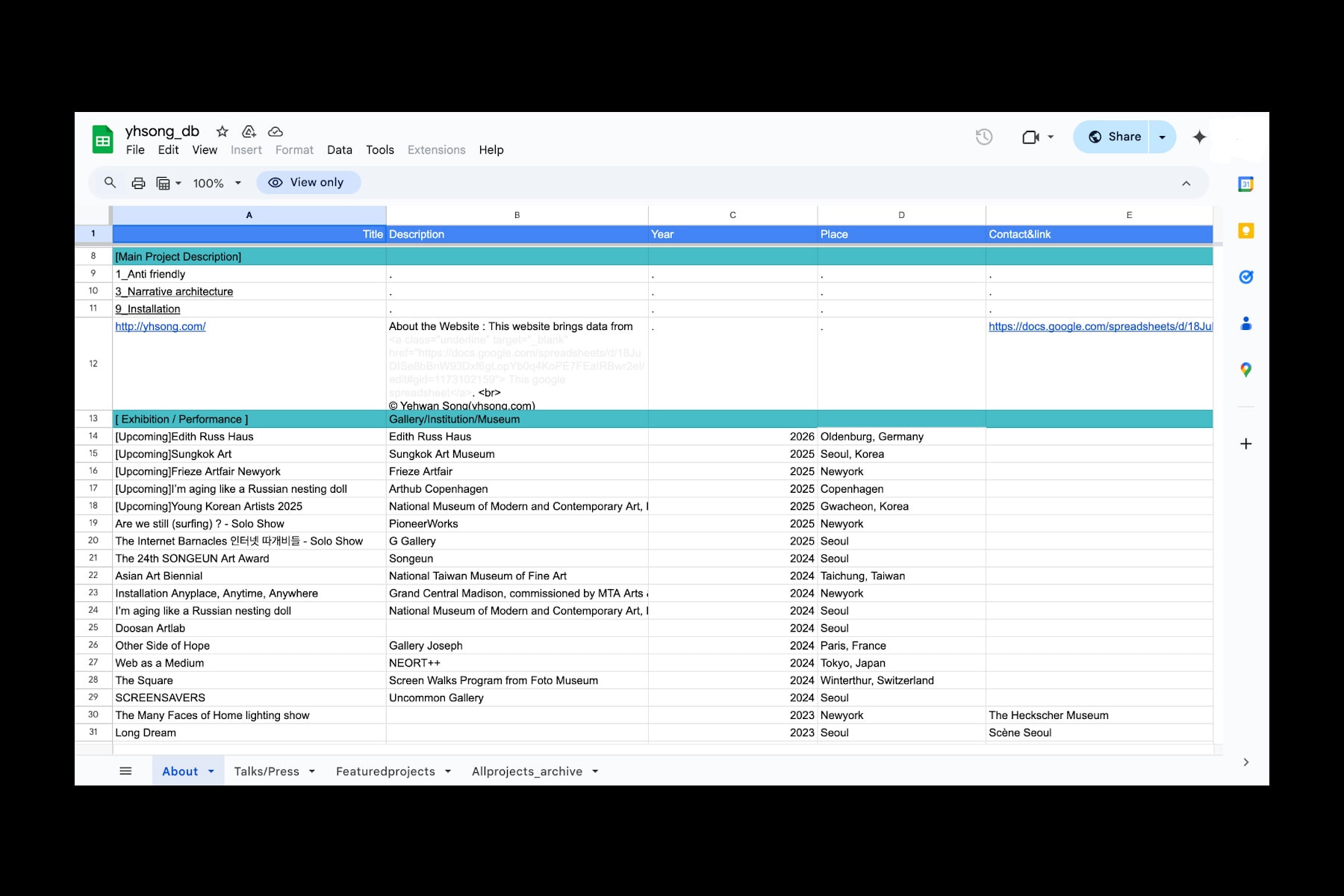

This marked a turning point. Instead of optimizing for efficiency or ease, Song started building work that completely disrupted expectations. Her browser-based projects don’t always respond to the user. They resist the frictionless legibility most sites strive for and ask users to slow down, pay attention and interact. Rather than send visitors to a traditional portfolio—which loads slowly—Song links her Instagram to a public Google Sheets document that pulls live content from her main website. Flattened into raw, chaotic cells, the database becomes a piece of web art: no hero image, tabs as navigation, and basic HTML markup.

“When I make something interactive as an artwork, the main purpose is to deliver something different or out-of-the-box,” she said. “It needs to be an experiment.”

Even in her earliest online projects, Song didn’t try to make websites that worked. She wanted to break them—to frustrate expectations, to interrupt passive consumption. Her “Anti User Friendly” series, including works like Speak Don’t Speak, challenges what a website should do. Buttons misbehave. Links reroute. Audio loops and stutters. These sites refuse smooth performance, and that friction is the point.

This isn’t glitches for glitches’ sake. Song’s sites aren’t broken. They make the system visible.

As Song continued to test the limits of browsers, she began to wonder about the frame itself. What happens when the screen doesn’t contain the work? What does it mean to design for disorientation in a room where projections spill onto the floor and interfaces lose their edges?

The “Barnacles” answer that call. It’s not a rejection of her web-based work, but a natural extension. Where her sites disrupt scrolling, the installation disrupts orientation. You can’t click your way through. You have to move.

“It’s not about changing the art. It’s about archiving it in a way that survives that environment.”

Song’s resistance to norms extends beyond her websites. It reaches into how her work circulates and who controls that circulation. Her projects often reject the platforms artists are told to use: social media grids, portfolio templates, tech apps that reward pay-to-play.

But making work that resists platforms doesn’t mean she can ignore them. “My work is about independent websites, but I still post on Instagram,” she explains.

She’s aware of the contradiction. Song doesn’t create work for social media, but she shares it there so people can see it. Instead of reshaping the art, she reshapes how it’s captured through looping GIFs, short videos that show collapse and motion, and the occasional sponsored post to fund materials. “It’s not about changing the art,” she said. “It’s about archiving it in a way that survives that environment.”

Still, she remains skeptical of relying on social platforms to circulate her work. “It’s not our database, it’s theirs,” she said. “We’re giving up our data, our formats, our context.” While she values digital archives (having learned from them herself), she also understands that trying to preserve websites can feel unnatural. She compares the internet to a river with its fluidity.

But the barnacles hold on. They don’t cling to stillness but attach to whatever carries them forward. Song doesn’t fix the internet’s instability or offer an escape. She leaves us mid-click, mid-thought, mid-drift—asking whether we’re navigating the web, or if it’s steering us.

Photography provided by G Gallery, Yehwan Song and Charlie Kane for Hypeart.