Dabin Ahn often wonders what his career would have looked like if his studies hadn’t been halted to enlist in the Korean Air Force. Prior to his mandatory service, the Seoul born artist primarily focused on portraiture, a creative inclination subconsciously driven by his overly obsessed self image, he recounts. As the son of Ahn-Sung Ki, one of Korea’s most prolific actors, young Dabin, who also pursued deejaying, lived a luxurious lifestyle and featured as a model in a number of prominent publications.

Two years of bootcamp, however, “is enough time to transform into someone else,” Ahn tells Hypeart, who couldn’t look at himself the same way after the military. “I used to spend like two hours every day trying to make myself look good. I was no longer interested in even looking at myself in the mirror.”

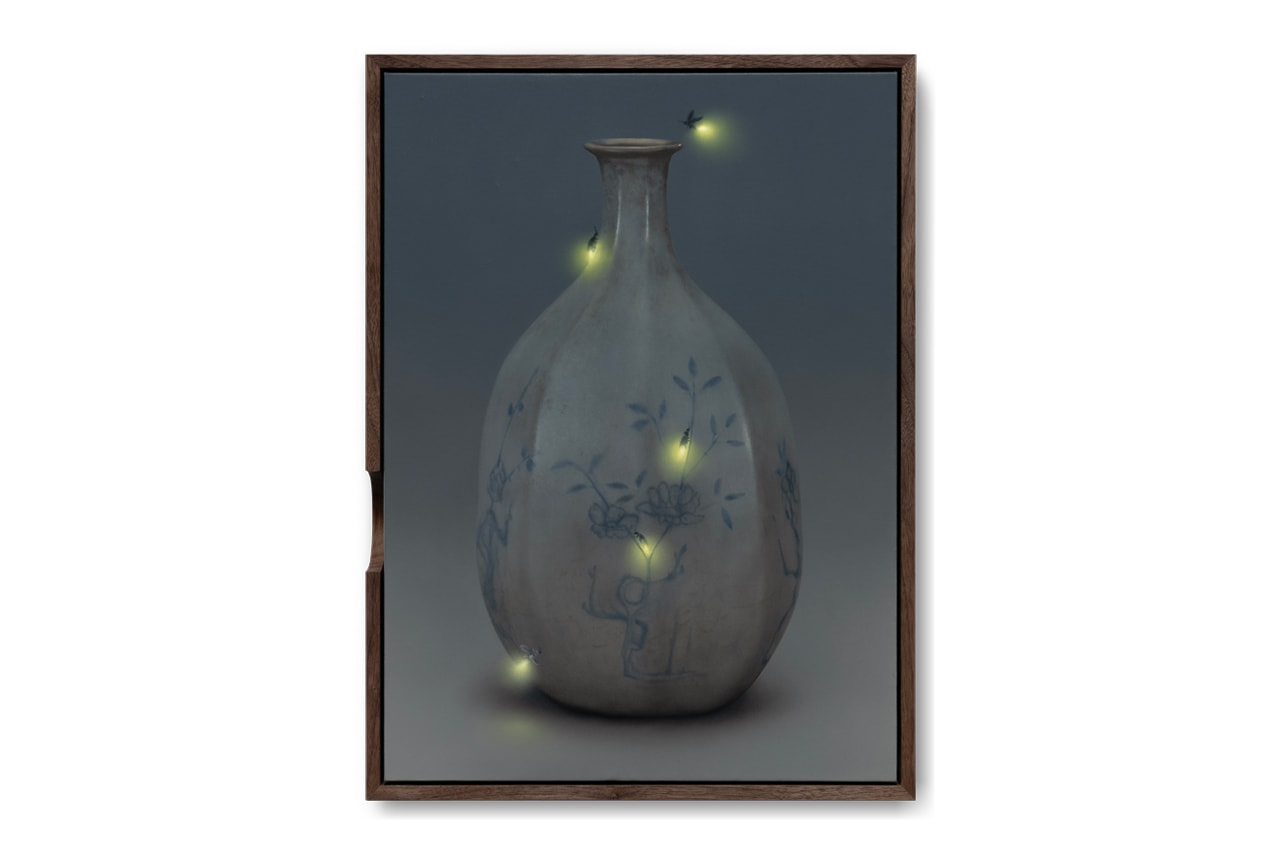

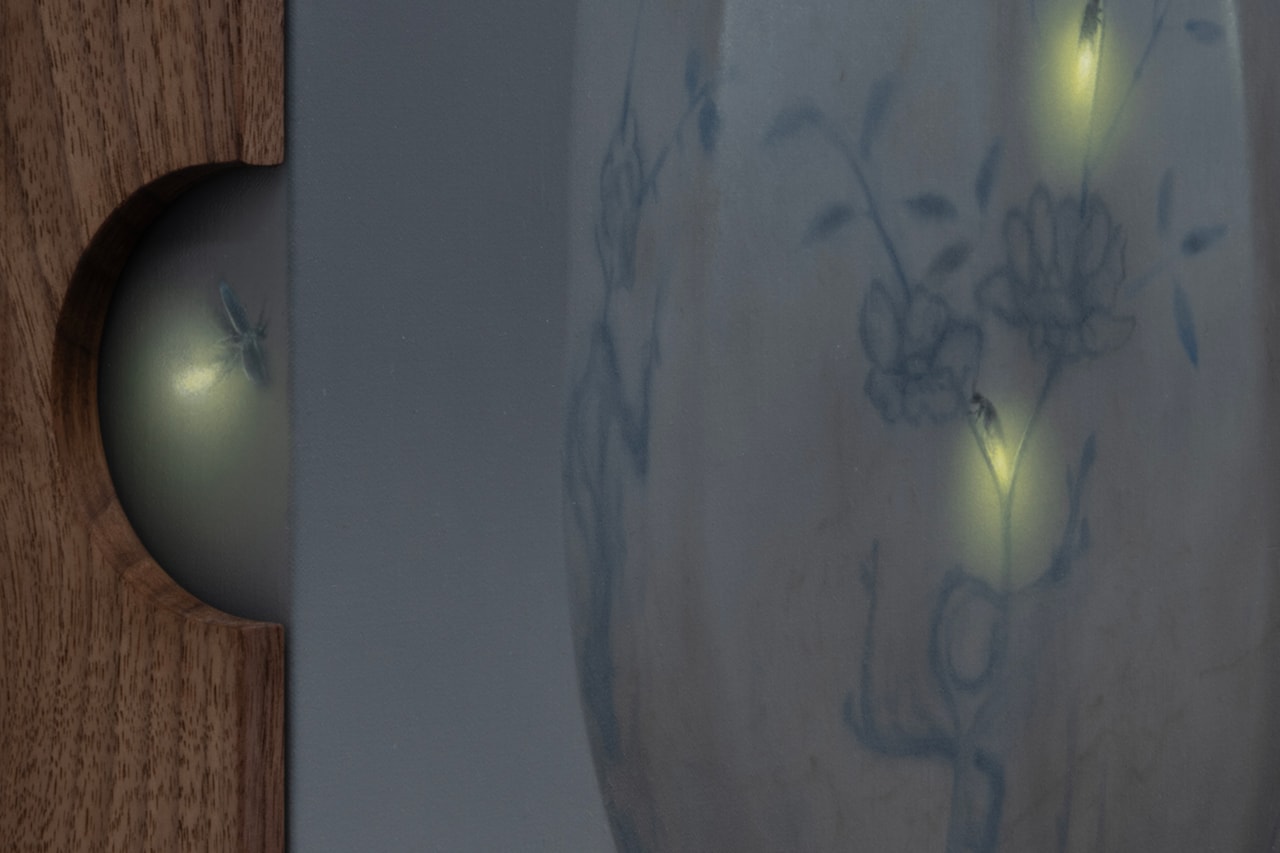

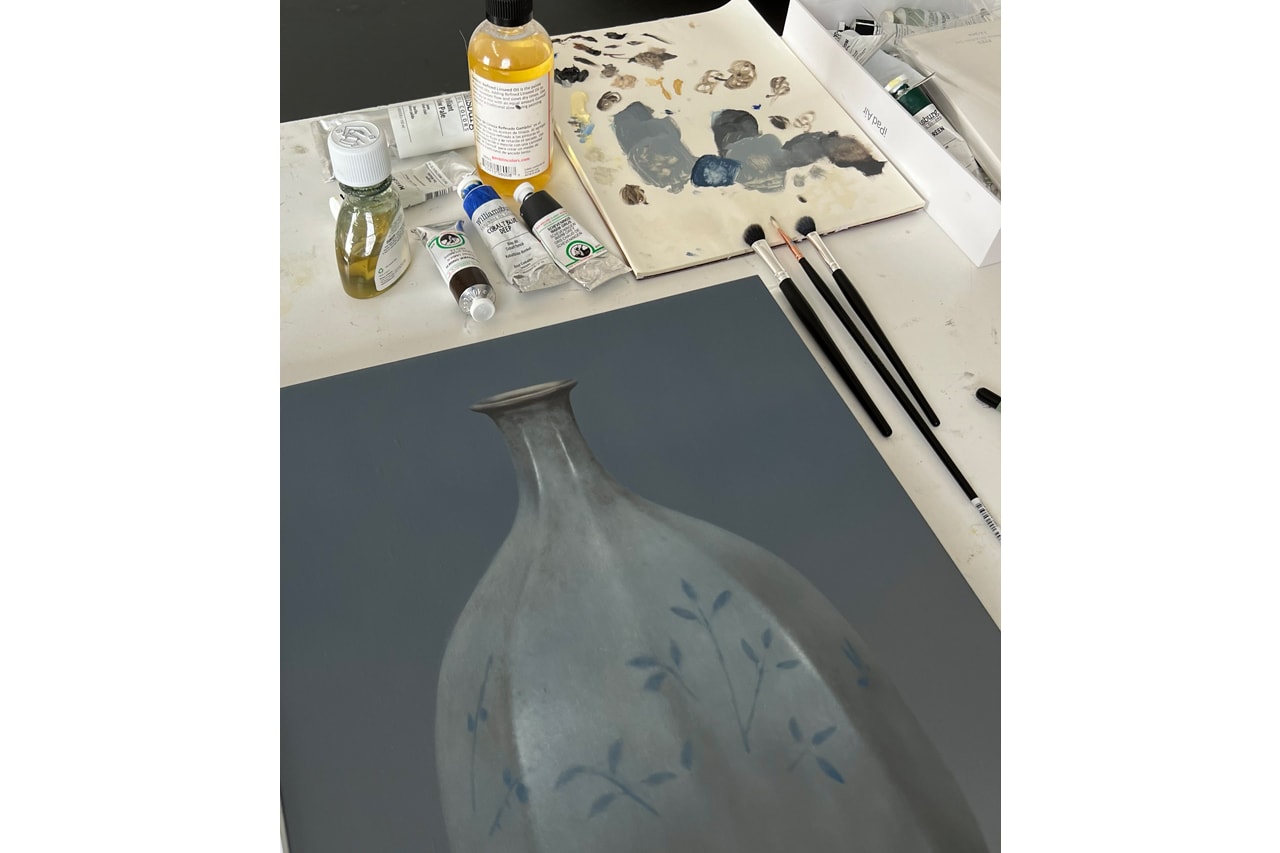

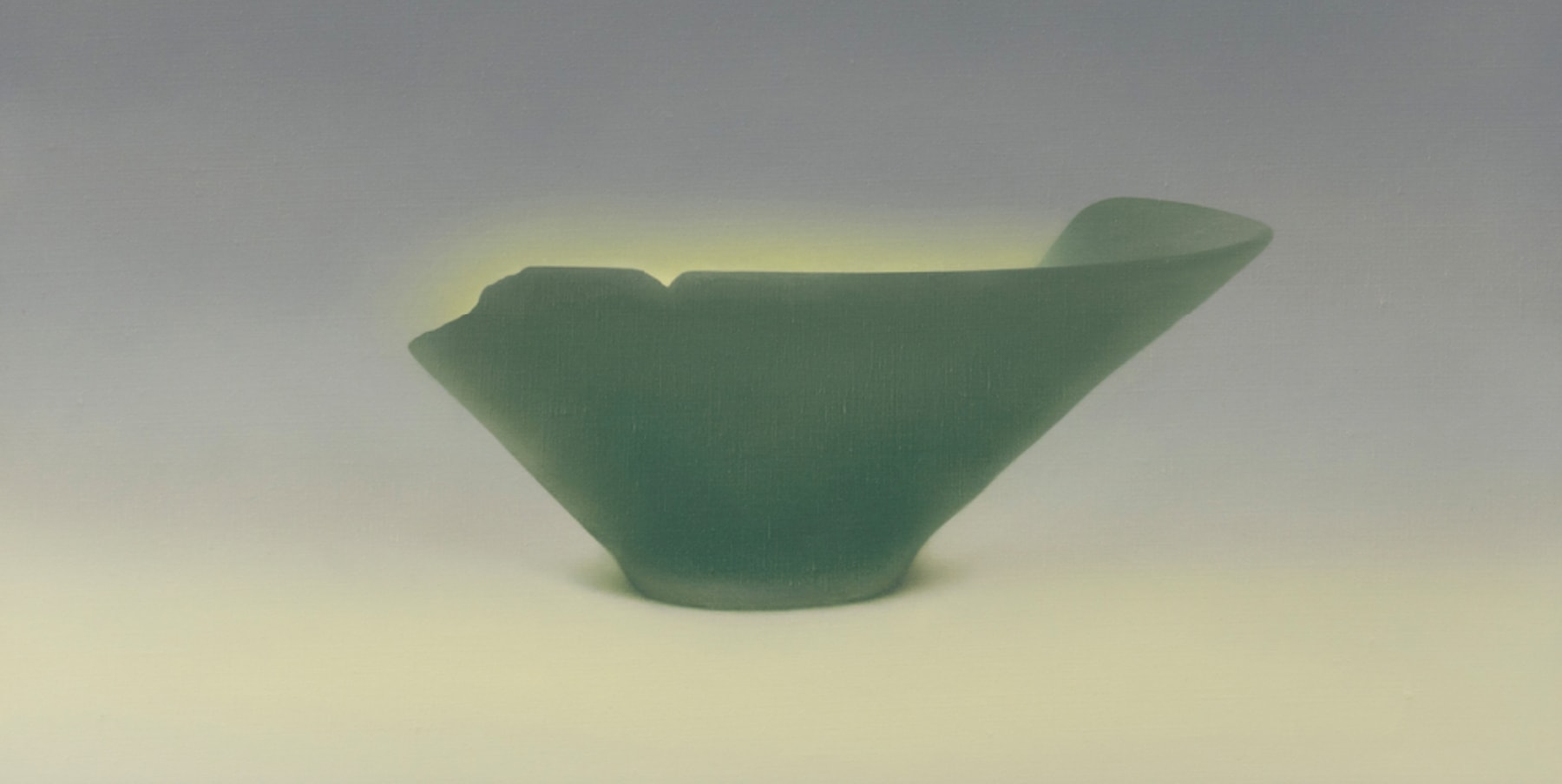

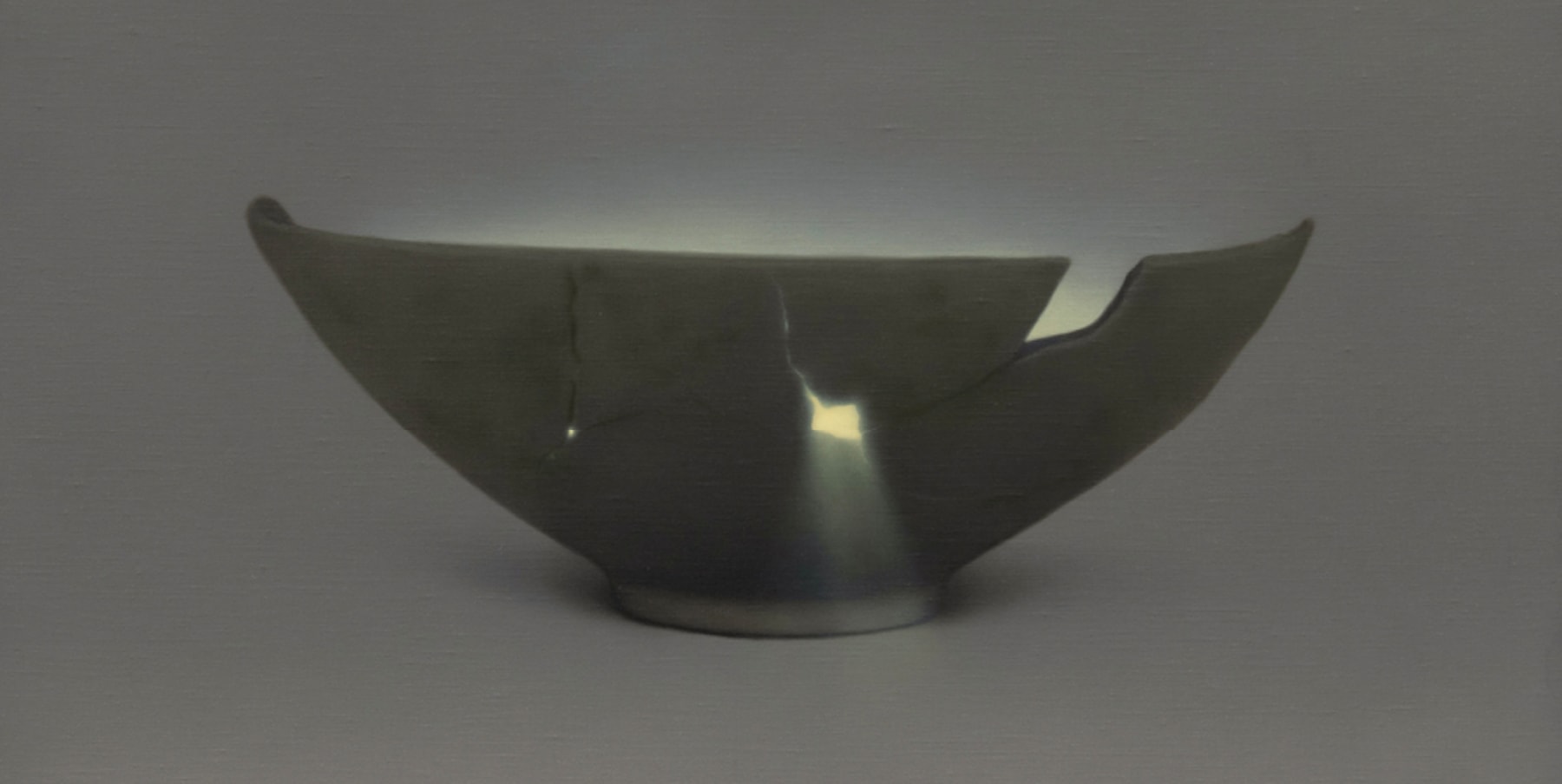

Stepping back into reality, Ahn returned to the U.S. where he received his BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He hasn’t left since and finds a sense of fulfillment and solace toiling away in his studio, where he splits his time between sculpture and painting, specializing in resin figures that appear as porcelain ceremonial miniatures, as well as misty still life paintings that look like photographs from a distant, but reveal blurry textures and contours upon closer inspection — images of twirling cranes and fauna, like hazy memories that get more vague with age.

Floating between physical vases or its illusionary two-dimensional canvas depiction, Ahn probes into the temporality of life, as he reflects on themes related to impermanence and imperfection. For the latest Hypeart Visits, we spoke with the rising Korean artist as he discusses the previously unforeseen merits his military service had in shaping his art career and how he creates vibrantly rich compositions, despite his partial color blindness.

Can you describe your transition from South Korea to the United States?

I was born and raised in Seoul, but started attending middle school in Boston at age 12. Then I went to high school in New Jersey and eventually studied at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. I was a painting major for my first two years of college, but as a Korean adult male, I had to serve in the military. So I spent the next two-and-a-half years in the Korean Air Force. That kind of messed up my momentum — which long story short, I was making a totally different body of work at that time, in contrast to what I’m making now.

I’m curious to know how my work would have evolved without the military influence in my life. I was discharged around 2011 and instead of returning to Pratt to finish my degree, I came to Chicago thinking that I would just complete my BFA and then either return to Chicago, Los Angeles or New York. Things just happened naturally. This is my tenth year in Chicago and the main reasons I stick around is I got my studio right after grad school.

“I’ve developed the habit of leaning into my strengths, rather than being afraid of my flaws.”

The world is so globalized today, where a pocket of London, New York, LA or Chicago are almost identical in terms of the people, the vibes, even the architecture. To touch back on your service: Do you think there were elements of your time in the military that reappear in your art today?

In boot camp, you’re given the same uniform and have to shave your head. They try to standardize everyone and ignore everything of what you used to be in society. In terms of social status, I was raised under a famous dad who used to be an actor in Korea. So people used to know me as the son of this famous actor — even in the military. And what they did is try to push me down all the way to the bottom, so that I didn’t feel that sense of entitlement among other people, who may have come from a less fortunate background than me in society.

So when I was doing self portraits, I was this narcissist who not only was into his own appearance, but also fond of my abilities and everything about myself. I loved myself. As I was in the military, I was yelled at, given punishments because I wasn’t doing what I was supposed to. I had never been treated in that way. Two years of that is enough time to transform into someone else. It’s that much information and that much influence.

Post-military, I couldn’t look at myself in the same way. I used to spend like two hours every day trying to make myself look good. I was no longer interested in even looking at myself in the mirror. So as far as my art, I replaced the subject, myself, with a still life.

I became interested in painting these beautiful perfect bowls or porcelain figurines, which transitioned into vessels that are either broken or have an imperfection that metaphorically resembles me in a way. In the past decade, I’ve gone through a lot of things, including my parents dealing with their illnesses. I’ve become more self-aware about aging. Things are not as glamorous as it used to be a decade ago.

Can you expand on your affinity for these “perfect” objects, like a porcelain vase — which also has a fragility to it.

I have color blindness in certain hues.

Psychologically, I understood it as a fatal flaw to have as a painter. It’s so ironic that a painter, who should be a professional at seeing colors, and who uses that paint to create an image, would be missing the color part. When I first found out about my color deficiency in high school, I was afraid of making the wrong color choices — in fear of people making fun of me — so I started to use just black and white. I made a lot of hyper-realistic drawings of broken glass. That was the starting point, which eventually pivoted to water drops on a glass surface. Slowly, color seeped its way back into my paintings.

Even today, my palette is pretty limited, where you don’t see bright yellow, orange or any highly saturated colors. That comes from the fact that I have color deficiencies, but now I’ve developed the habit of leaning into my strengths, rather than being afraid of my flaws.

Which colors do you have a deficiency in?

Mostly reds and greens. So very hard to see colors in nature. I appreciate paintings and photographs that capture nature less. It’s well-known that Daniel Arsham is also colorblind and I know a few other people who I’m friends with, who are as well. Something we have in common is that we are so into either fabrication or rendering without the use of vibrant colors.

I think people naturally find other talents when they have certain deficiencies. That’s exactly what happened to me. It felt good when I was able to finally finish my first painting that looked so real that people were complimenting how they looked like photographs. As a 19-year-old, that was what I wanted to hear. Of course, right now, that’s what I don’t want to hear from people — because if that’s the only feedback, then I’m clearly not getting my messages across. The emotion that I’m creating through my new series of paintings tell a slightly different story: touching on themes related to aging and how I miss a lot of things as I’m getting further away from my older memories.

“I still can’t verbally express what my practice is about and my life goal is to find that.”

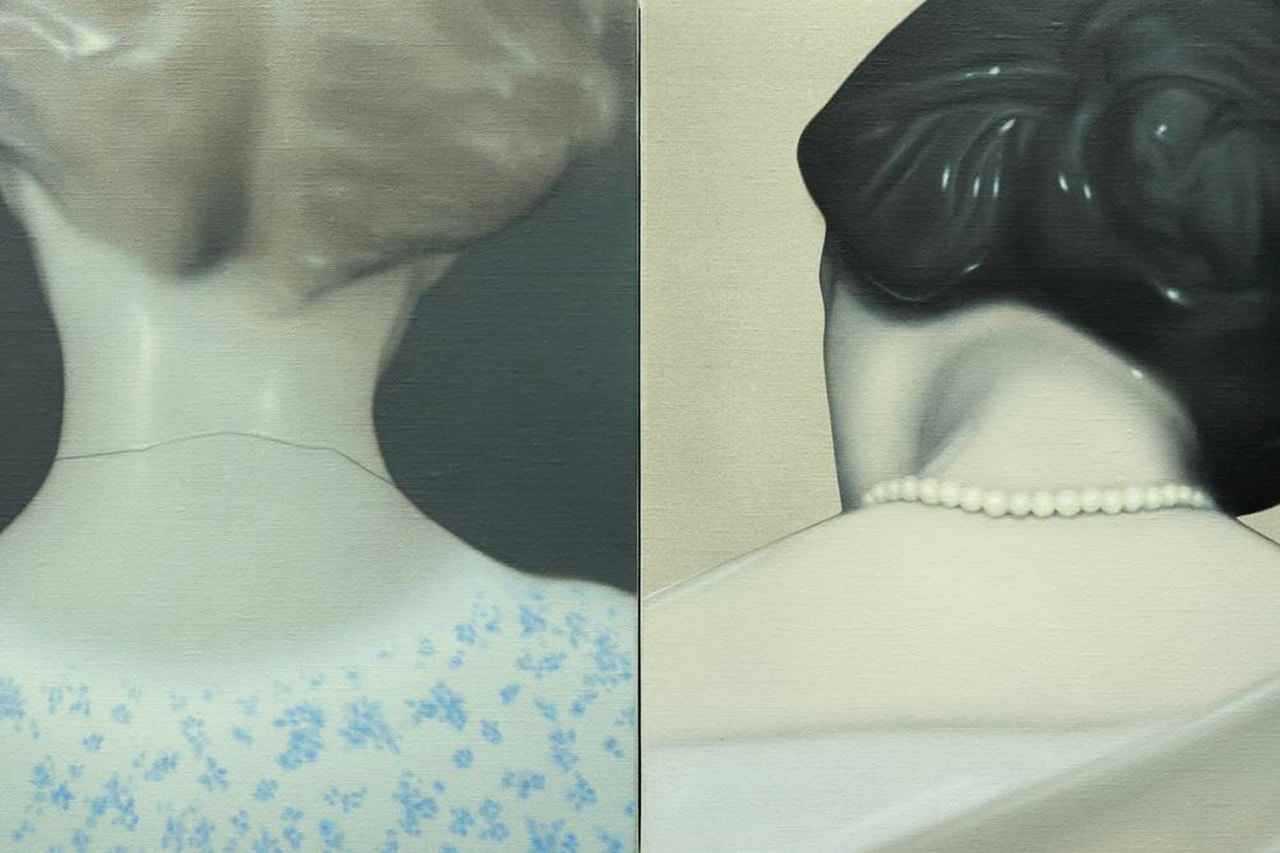

There are specific iconography you use, such as cranes or cropped-in images of a woman’s neck or feet tap dancing. Can you discuss the reasons behind your figurative choices?

I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to present two years ago. So I naturally drew from my childhood, vividly recounting my mother’s small collection of dinnerware, like porcelain plates, cups, bowls and other things imported from Western countries through a Korean point of view. Exposure to these foreign objects at an early age had a great Impact on me and so my general interest in porcelain started very early.

That’s how I got introduced to all these shiny perfect-looking objects. So my general interest in porcelain started very early. And when I graduated from my MFA program, I just wasn’t ready to jump on a new subject. So I started painting vessels again and expanded my subject matter from cups and vases to figurines with facial features. It was another carrier that I could apply my own emotions into. The brand and year these figurines were made in wasn’t important. But I did need something to pour my thoughts into — something both anonymous and almost like a blank canvas.

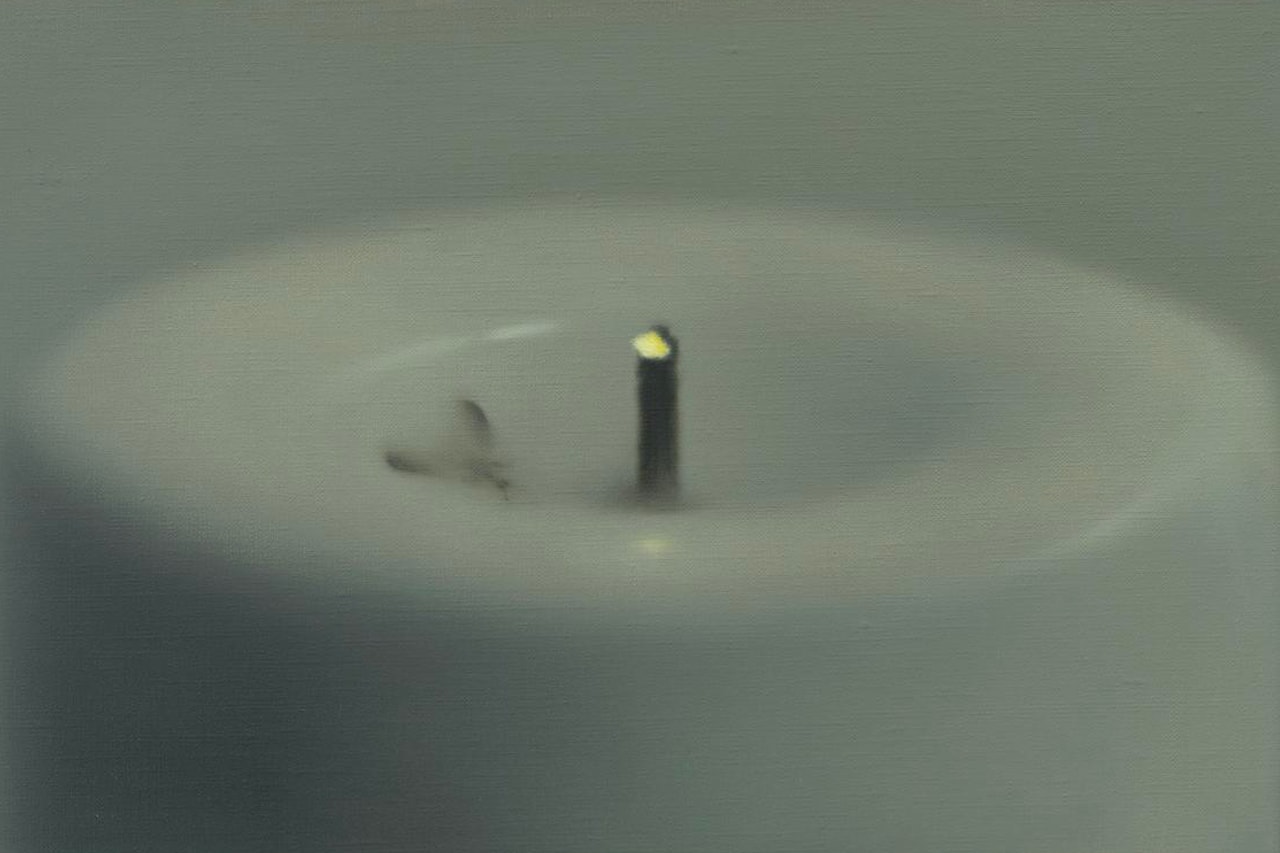

It felt like I could put any meaning into these figurines if I cropped it in a certain way, or if I turned it around and painted the backside with like an added crack on the neck, resulting in a new narrative. I did that for about a year until having another breakthrough in summer of 2023, when I made my first candle painting.

It felt like I could put any meaning into these figurines if I cropped it in a certain way, or if I turned it around and painted the backside with like an added crack on the neck, resulting in a new narrative. I did that for about a year until having another breakthrough in summer of 2023, when I made my first candle painting. My college professor used to say: “Dabin I think you’re trying so hard to make a masterpiece. You don’t have to. Just start with a small painting and see where it takes you.” It’s been four years now that I’ve been making small-sized paintings — and it’s not like I don’t have the ability to scale up — but there is something I’m learning through this current approach. I see it as a long process of being invested in these vessels. I still can’t verbally express what my practice is about and my life goal is to find that.

Unlike design, which presents solutions to problems, art can be any and everything — and is often a question the individual poses to the world from within. It’s interesting you say that your life’s work is to be able to define your practice, but at the same time, it’s not something that necessarily has to happen to be fruitful.

If someone needed an artist statement from me, I’ll provide it. But it won’t have a conclusion. It’s only going to describe how I felt in that particular moment.

Can you describe your process, from first thought to final execution?

I’m careful to say how long it takes to make a particular painting, because I don’t want to mislead people thinking it’s easy. With this new candle series, I’ve become pretty comfortable in the painting process, considering they’re not too big. So the process can be fairly quick, maybe about a week. But at the same time, the people who know me know that I’m in the studio all day — first one in, last one out. Whatever the deadline, I’ll always meet it.

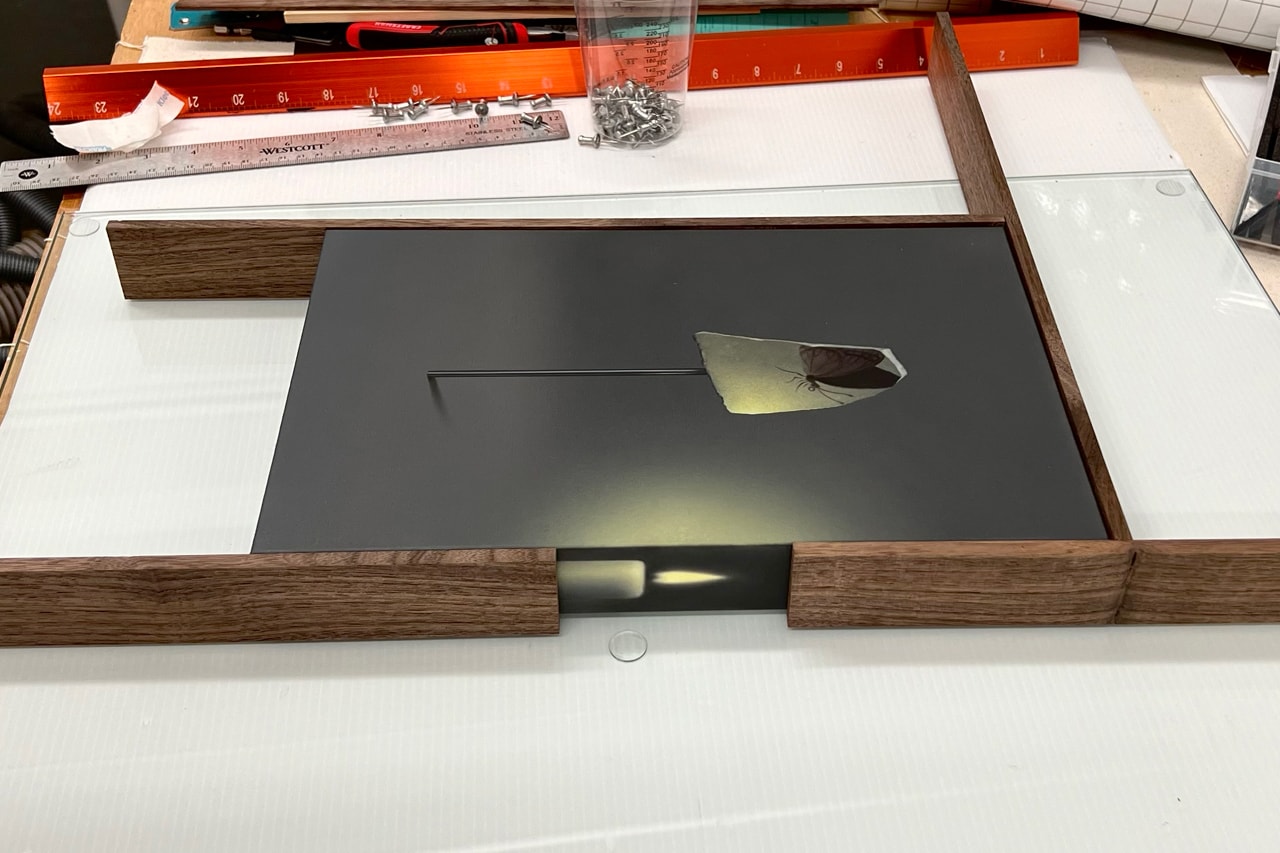

It’s interesting how you extend the central image of the paintings to the sides of the canvas, such as the candle works — where those tiny slivers of space take on an almost equal dialogue with the central image. How did this develop?

Aside from the canvas and paints, everything else is done within my studio. A one man job — from going to Home Depot to get raw lumber to using power tools to build stretchers from scratch, stretching linen over it and then starting the painting process.

I’m not against it, but if you’ve never fabricated or haven’t gone through the process of building a stretcher, stretching canvas over it, and then painting it — it’s an entirely different feeling. It’s like building a car on your own and going on that first ride, versus just buying a car from the lot. Or auto versus manual. So there’s a quality of physically building the object. To me, the canvas is like a sculptural object, parched with emotions and energy, even before I put an image on it.

I’m a photographer as well. So I’ll photograph my work and send those to the galleries who need it. I find a lot of happiness in the process.

All artwork courtesy of Dabin Ahn for Hypeart.